In modern enterprise infrastructure, a single server failure can cascade into catastrophic downtime. Enter the Virtual IP (VIP), a floating address architecture that has become the cornerstone of high availability systems worldwide. Unlike traditional physical IP addresses bound to specific network interfaces, a VIP operates as an abstraction layer that can seamlessly migrate between servers without requiring client reconfiguration.

When combined with load balancing, VIPs transform static server farms into dynamic, self-healing networks capable of distributing millions of requests per second. Whether you are architecting a global content delivery network or ensuring zero-downtime deployments for critical applications, understanding what is a Virtual IP (VIP) and how does load balancing work is essential for any network engineer in 2026. This guide deconstructs the technical mechanisms behind VIP failover, Layer 4 versus Layer 7 load balancing, and the forensic architecture powering enterprise-grade availability.

"After two decades deploying mission-critical infrastructure, I've witnessed VIP architectures evolve from simple failover scripts to sophisticated Anycast networks spanning continents. The most common mistake engineers make is treating VIPs as mere IP aliases. In reality, a properly configured VIP ecosystem involves health check orchestration, BGP route injection, and sub-second failover mechanisms that can mean the difference between 99.9% and 99.999% uptime."

The Quick Resolution: Understanding VIP Load Balancing

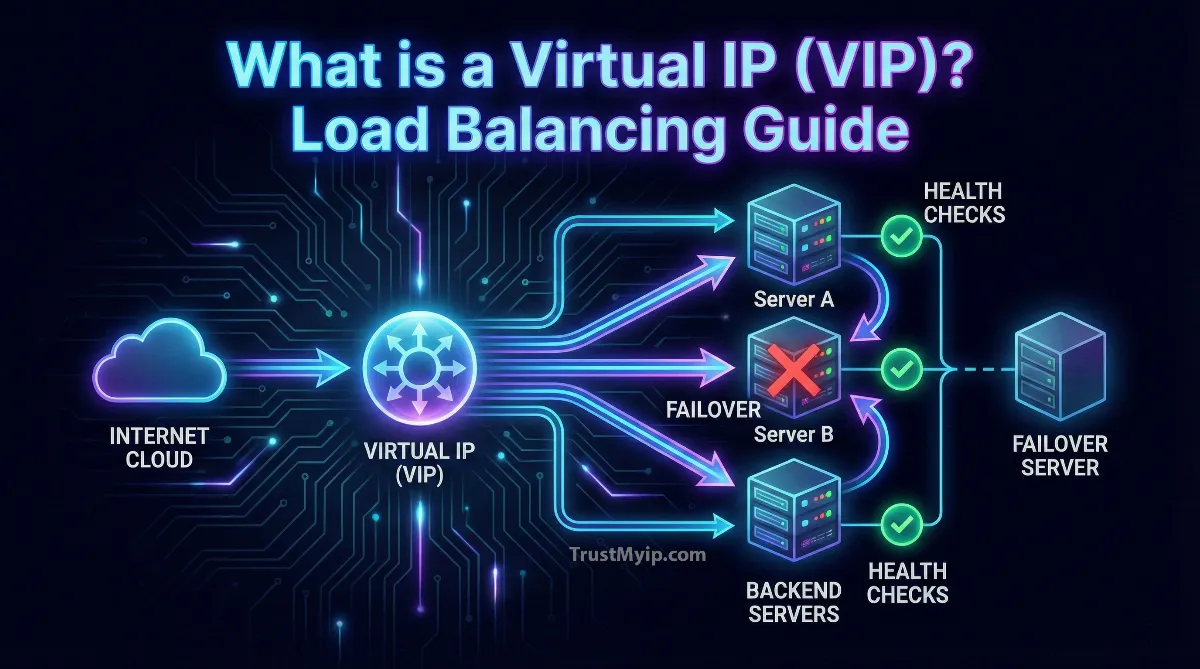

A Virtual IP (VIP) is a floating IP address not bound to any specific network interface, managed by a load balancer that distributes incoming traffic across multiple backend servers. This architecture enables automatic failover, horizontal scaling, and transparent maintenance without client disruption. Modern implementations use health checks, session affinity, and intelligent routing algorithms to ensure requests always reach healthy servers.

1. What is a Virtual IP Address? The Floating Network Identity

A Virtual IP (VIP) represents a paradigm shift from traditional networking where IP addresses were permanently assigned to physical hardware. Instead, a VIP acts as a logical entry point that can dynamically move between multiple servers based on availability and load conditions.

Physical IP vs Virtual IP: The Core Difference

When you assign a physical IP address like 192.168.1.100 to a server's network interface card, that binding persists until manually changed. If the server crashes, that IP becomes unreachable. A VIP like 10.0.50.200 exists independently of any single machine. Using protocols like VRRP (Virtual Router Redundancy Protocol) or CARP (Common Address Redundancy Protocol), multiple servers can share ownership of the VIP, with only one actively responding at any given time.

How VIP Failover Works at the Network Layer

When the primary server holding a VIP fails, the backup server immediately broadcasts a Gratuitous ARP (GARP) packet to the network. This forces all switches and routers to update their ARP cache tables, remapping the VIP's MAC address to the new server's interface. This process typically completes in under 3 seconds, making the failover nearly transparent to end users. Learn more about network protocols in our guide on how DNS resolves domain names to IPs.

2. Load Balancing Fundamentals: Traffic Distribution Architecture

A load balancer sits between clients and servers, intercepting all traffic destined for the VIP and intelligently routing it to healthy backend nodes. This creates a single point of management while distributing the actual computational load.

Modern load balancers operate at different layers of the OSI model, each offering distinct capabilities:

- • Layer 4 (Transport Layer): Routes based on IP address and TCP/UDP port without inspecting packet contents. Fastest performance but limited routing intelligence.

- • Layer 7 (Application Layer): Examines HTTP headers, cookies, and URL paths to make sophisticated routing decisions. Enables advanced features like SSL termination and content-based routing.

- • DNS-Based Load Balancing: Returns different IP addresses in DNS responses to distribute traffic geographically, though lacks real-time health awareness.

- • Global Server Load Balancing (GSLB): Coordinates traffic across multiple data centers using latency-based routing and disaster recovery failover.

The Request Flow: Client to VIP to Backend

When a client sends a request to a VIP like 203.0.113.50, the load balancer receives the packet first. It consults its server pool (also called a backend farm) to select a healthy target based on the configured load balancing algorithm. The load balancer then either proxies the connection (creating two separate TCP sessions) or uses Direct Server Return (DSR) mode where responses bypass the load balancer entirely, returning directly to the client.

3. Load Balancing Algorithms: How Traffic Gets Distributed

The algorithm determines which backend server receives each incoming request. Choosing the right algorithm impacts both performance and user experience, especially for stateful applications requiring session persistence.

| Algorithm | Distribution Logic | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Round Robin | Cycles through servers sequentially in order. | Stateless apps with equal server capacity |

| Least Connections | Routes to server with fewest active sessions. | Long-lived connections (WebSockets, databases) |

| IP Hash | Hashes client IP to consistently route to same server. | Session affinity without cookies |

| Weighted Round Robin | Assigns traffic proportionally based on server capacity ratings. | Heterogeneous server hardware |

| Least Response Time | Routes to server with lowest latency and fewest connections. | Performance-critical applications |

4. Health Checks: Ensuring Traffic Only Reaches Healthy Servers

A load balancer continuously monitors backend servers using health check probes to automatically remove failed nodes from rotation. This prevents clients from being routed to unresponsive servers, maintaining service availability even during partial infrastructure failures.

Health Check Mechanisms

TCP Connect: Verifies the server accepts connections on the service port (e.g., port 80 for HTTP).

HTTP GET: Requests a specific URL and validates the response code is 200 OK.

HTTPS with Certificate Validation: Ensures SSL certificates are valid and not expired.

Custom Scripts: Executes application-specific logic to verify database connectivity or cache availability.

Passive Monitoring: Observes actual client traffic patterns to detect degraded performance before complete failure.

When a server fails three consecutive health checks (configurable threshold), the load balancer marks it as down and stops routing traffic to it. Once the server recovers and passes health checks again, it automatically rejoins the pool. This self-healing capability is fundamental to achieving five-nines availability (99.999% uptime).

5. Advanced VIP Architectures: High Availability Patterns

Enterprise deployments combine multiple VIPs, load balancers, and failover strategies to eliminate all single points of failure. These architectures ensure continuous operation even during planned maintenance or unexpected hardware failures.

Production-Grade VIP Deployment Patterns

- Active-Passive Failover: Two load balancers share a VIP using VRRP. The active unit handles all traffic while the passive unit monitors health and assumes control if the primary fails.

- Active-Active with ECMP: Multiple load balancers advertise the same VIP via BGP, with upstream routers distributing traffic using Equal-Cost Multi-Path (ECMP) routing for true horizontal scaling.

- Geographic Distribution: VIPs assigned in multiple regions with Anycast routing directing users to the nearest healthy location based on network topology. Check our complete guide to Anycast routing.

- Cloud-Native Load Balancing: Platforms like AWS ELB, Azure Load Balancer, and Google Cloud Load Balancing provide managed VIP services with automatic scaling and multi-zone redundancy.

6. Session Persistence: Maintaining Stateful Connections

Many applications store session data locally on the server handling a user's initial request. Without session persistence (also called sticky sessions), subsequent requests from the same user might land on different servers lacking their session context, causing login failures or lost shopping carts.

Load balancers implement session persistence through several mechanisms:

- • Cookie-Based Persistence: Injects a cookie containing the selected backend server ID, ensuring return requests reach the same server.

- • Source IP Affinity: Hashes the client's IP address to consistently route to the same backend, though NAT networks can cause multiple users to share IPs.

- • SSL Session ID Persistence: Tracks encrypted session identifiers to maintain HTTPS connections to the same backend for the entire SSL session.

- • Application-Level Tokens: Uses URL parameters or custom headers set by the application to encode routing decisions.

The tradeoff with session persistence is reduced load distribution flexibility. If one server handles many long-running sessions, it may become overloaded while others remain idle. Modern architectures address this by storing session state in external caches like Redis or databases, making all backends stateless and eliminating the need for sticky sessions. For more on IP-based routing, see our article on MAC address versus IP address differences.

7. SSL Termination and Offloading: Optimizing Backend Performance

Encrypting and decrypting HTTPS traffic consumes significant CPU resources. By performing SSL termination at the load balancer, backend servers receive plain HTTP requests, freeing their processing power for application logic rather than cryptographic operations.

SSL Termination Workflow: Client establishes HTTPS connection to the VIP. The load balancer presents its SSL certificate, completes the TLS handshake, and decrypts the traffic. It then forwards the request to backend servers over unencrypted HTTP within the trusted internal network. Responses follow the reverse path, with the load balancer re-encrypting before sending to the client.

This architecture centralizes certificate management at the load balancer, eliminating the need to distribute private keys to every backend server. For additional security, some deployments use SSL bridging where traffic is re-encrypted between the load balancer and backends, though this reduces performance benefits.

8. Direct Server Return: Bypassing the Load Balancer for Responses

In standard proxy mode, both request and response traffic flow through the load balancer, which can become a bottleneck for bandwidth-intensive applications like video streaming. Direct Server Return (DSR) allows backend servers to send responses directly to clients, bypassing the load balancer entirely.

DSR Technical Implementation

Step 1: Load balancer receives packet destined for VIP 10.0.50.200.

Step 2: It selects backend server 192.168.1.10 using the configured algorithm.

Step 3: Instead of proxying, it rewrites only the destination MAC address to the chosen server's interface, leaving the VIP as the destination IP.

Step 4: Backend server must have the VIP configured as a secondary address on a loopback interface.

Step 5: Server processes the request and sends the response directly to the client's IP, with the VIP as the source address.

Result: Client receives response appearing to come from the VIP without traversing the load balancer again.

DSR dramatically reduces load balancer bandwidth requirements since only inbound requests consume its resources. The limitation is that it only works for Layer 4 load balancing and cannot modify application-layer content. It also requires all servers to be on the same Layer 2 network segment as the load balancer.

9. VIP in Cloud Environments: AWS, Azure, and GCP

Cloud platforms restrict traditional networking protocols like Gratuitous ARP, requiring different approaches to VIP implementation. Each provider offers managed load balancing services that abstract the underlying complexity while providing VIP-like functionality.

Cloud Load Balancer Comparison

- AWS Elastic Load Balancer (ELB): Offers Application Load Balancer for Layer 7 HTTP routing, Network Load Balancer for Layer 4 TCP/UDP, and Gateway Load Balancer for transparent network appliance insertion. Automatically scales capacity and integrates with IP address management.

- Azure Load Balancer: Provides Standard SKU with zone redundancy, automatic failover across availability zones, and integration with Azure Traffic Manager for global load balancing using DNS-based routing.

- Google Cloud Load Balancing: Features global Anycast VIPs that route users to the nearest region automatically, with cross-region failover and integrated DDoS protection through Cloud Armor.

- Kubernetes Services: Implements VIP functionality through ClusterIP and LoadBalancer service types, with ingress controllers providing Layer 7 routing and automatic certificate management via SSL validation.

10. Troubleshooting VIP and Load Balancer Issues

When VIP architectures fail, diagnosing the root cause requires systematic analysis of network layers, health check status, and traffic flow patterns. Common failure modes have distinct symptoms that guide troubleshooting.

- VIP Not Responding: Verify the load balancer is running and the VIP is configured correctly. Use ping tests to check Layer 3 connectivity and ARP tables to confirm MAC address resolution.

- Unbalanced Traffic Distribution: Review algorithm configuration and server weights. Check if session persistence is inadvertently routing all requests from a NAT gateway to the same backend. Monitor real-time connection counts with port scanning tools.

- Health Checks Failing: Examine backend server logs for errors preventing health check responses. Verify firewall rules permit traffic from the load balancer's IP address. Test health check URLs manually from the load balancer itself.

- SSL Certificate Errors: Ensure certificates installed on the load balancer match the VIP's hostname and haven't expired. For multi-domain setups, verify Subject Alternative Names (SANs) cover all required domains.

- Source IP Visibility Issues: If backends need to see original client IPs, enable X-Forwarded-For headers at Layer 7 or use Proxy Protocol at Layer 4. For debugging, use our HTTP headers analyzer.

Conclusion: Building Resilient Infrastructure with VIPs

Understanding what is a Virtual IP (VIP) and how does load balancing work is fundamental to designing modern high availability systems. VIPs decouple service identity from physical hardware, enabling seamless failover and maintenance without client impact. When combined with intelligent load balancing algorithms, comprehensive health monitoring, and strategic deployment patterns, VIP architectures form the backbone of internet-scale services processing billions of requests daily. Whether deploying on-premises hardware load balancers or cloud-native solutions, the principles remain constant: distribute traffic intelligently, monitor continuously, fail over automatically, and scale horizontally. As applications grow more complex and uptime expectations approach absolute reliability, mastery of VIP and load balancing technologies separates resilient infrastructure from fragile single points of failure.

Test Your Network Infrastructure!

Verify your load balancer configuration, check backend server connectivity, and monitor real-time traffic distribution with our professional network diagnostic toolkit.